Friday Feature: The Role of a Commission in College Sports

Do We Really Need Yet Another Commission? House v. NCAA is about to rewrite every rule of college compensation. Whether a blue-ribbon panel can, or even should, police the new system is the question.

When word leaked that the White House was drafting an executive order to create a “Presidential Commission on College Sports” with Nick Saban and Texas billionaire Cody Campbell rumored as co-chairs, reactions ranged from hope to déjà vu. ESPN analyst Jay Bilas probably spoke for a weary industry when he told On3, “Anything with commission on it is probably not going to accomplish anything.”

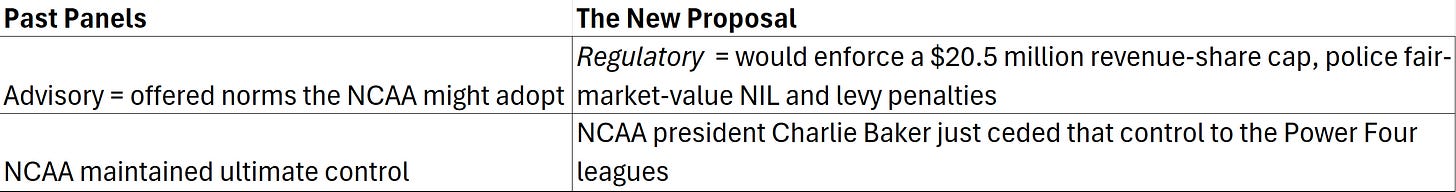

His cynicism is earned. The Knight Commission (b. 1989) produced shelves of reports on academic integrity, yet never stemmed the revenue avalanche. The Rice Commission (2018), chartered to “clean up” basketball after the FBI sting, promised a hard reset; three years later, NIL arrived, and the sport plunged into open-market chaos. Neither body had rule-making power, budgetary teeth, or the ability to preempt state law. Both became think-tanks whose recommendations the NCAA could cherry-pick or ignore.

Now comes the latest curveball: according to Yahoo’s Ross Dellenger, the White House has “paused” the drafted executive order, at least temporarily, to avoid spooking a five-senator working group (Cory Booker, Ted Cruz, et al.) that is still chasing a bipartisan NIL bill. Invitations for commission membership had already gone out, and Campbell met with Saban last week, but everything is now on hold “until further notice.”

Pause or no pause, “commission” talk is not going away, because on the eve of Judge Claudia Wilken’s expected approval of the House settlement, the NCAA has floated a different model:

“The point … was to create an entity that would see the cap-management system and the third-party NIL system, have rules associated with both, [and] create enforcement parameters,” Baker told the Knight Commission last week.

In other words, the goal of the new commission would be that the NCAA step aside once the settlement is approved; the real commission, dubbed the College Sports Commission in draft documents, will be owned and staffed by the ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, and SEC. Think of it as a quasi-league office for a 130-school professionalized subdivision.

Why a commission could matter this time

The settlement’s injunctive relief is only safe from immediate antitrust attack if an independent body monitors compliance. Judge Wilken all but demanded an arbiter capable of auditing rosters, caps, and booster contracts. A league-run commission supplies that mechanism, and crucially, gives plaintiffs somewhere to complain before racing back to court. Moreover, markets hate legal patchwork. The commission’s “single portal” for NIL contracts (with Deloitte as FMV auditor) would override Tennessee-style shield statutes by contract, requiring every member school to waive conflicting protections as a condition of Power-Four membership.

From a disciplinary standpoint, the new body can fine, withhold CFP revenue, or ban postseason play without dragging the entire Association back into federal discovery. That lowers litigation risk and avoids repeating the NIL-recruiting injunction the NCAA just lost to Tennessee’s attorney general. Also, cap ledgers, collective contracts, and revenue-share distributions would live on one dashboard, which creates the first comprehensive database of athlete pay, serving as a prerequisite for Title IX audits and future collective bargaining.

The counter-argument: Commissions do not write checks or pass laws

Saban, the man tabbed to run the presidential version, is lukewarm on the idea. “We know what the issues are, we just have to have people who are willing to solve them,” he told reporters at his Nick’s Kids charity event, adding that he would rather serve as a consultant than chair a bureaucracy.

His reluctance spotlights three structural flaws. First, no supremacy clause. A commission cannot invalidate state statutes. Tennessee’s new NIL-shield law explicitly indemnifies its universities if they ignore House caps, and the legislature has no incentive to retreat. The SEC and its peers have floated a “loyalty pledge” (sign or face expulsion), but forcing Knoxville out could invite antitrust counter-suits and political backlash.

Next, capture risk. Because the leagues fund the commission, enforcement could skew toward protecting TV inventory, not competitive balance. Will a $100 million football powerhouse ever be barred from the CFP because it exceeded the cap by $3 million? History (see North Carolina’s academic scandal or Kansas basketball’s infractions case) suggests otherwise.

Lastly, the collective-action threshold. The House settlement is an opt-in deal. If even one Power-Four conference balks at the new supervisory regime, the cartel fractures and schools platform-shop for more lenient rules. The commission’s authority lasts only as long as its members’ patience.

What courts (and Congress) will weigh

The commission’s rulebook must navigate four doctrines:

Antitrust – The Supreme Court’s Alston decision (2021) taught that NCAA-wide restraints on pay invite per-se condemnation unless tied to a concrete, pro-competitive justification. A Power-Four-only restraint may fare slightly better because the relevant market is narrower, but the cap will still be scrutinized under the Rule of Reason. A transparent, enforceable program helps, but does not guarantee, survival.

Labor law – The National Labor Relations Board’s Los Angeles office has already issued a complaint labeling USC football players “employees.” A commission could become the management negotiator if student-athletes unionize; absent that, its unilateral caps risk being recast as illegal wage-fixing.

Title IX – Equal-opportunity statutes apply once dollars flow through institutional accounts. The commission can dictate that a woman’s rowing scholarship counts the same as a football stipend, but any imbalance could produce class-action exposure.

State NIL statutes – Conflict-of-laws questions will proliferate. A contract clause that forces universities to waive state protections may be unenforceable if the legislature deems it contrary to public policy.

How yesterday’s “pause” changes the calculus

As long as Booker, Cruz & Co. hunt for a federal NIL bill, the White House will not crowd the lane. That nudges leverage back to Capitol Hill, which is bad news for leagues hoping a presidential order would preempt shield states. If the Trump-Campbell body stalls, Baker’s College Sports Commission is now the only concrete enforcement blueprint ready for July 1 implementation. Judge Wilken could rule any week. The Power Four must finalize bylaws, staffing, and penalty matrices fast, or risk a cap launch with no policeman.

So, commission or chaos?

Bilas is right that blue-ribbon panels rarely deliver sweeping reform, but this commission would not be a think tank. Rather, it would be a quasi-league office empowered by private contract and federal court order. That alone distinguishes it from the Knight or Rice efforts.

Still, structure alone cannot solve college sports’ existential dilemma: how to share billions while satisfying 50 statehouses, 1,100 schools, and a judiciary allergic to collusion. A commission offers a sandbox for experimentation with salary-cap algorithms, NIL valuation tools, and revenue audits, but it cannot preempt Congress or tame booster checkbooks overnight.

Whether the new body becomes a guardian of competitive balance or just another acronym depends on a few variables, with the first being Judge Wilken’s injunction language. If she embeds the commission in her final order, its authority becomes federal law. If she merely “takes note,” the leagues are on their own. Moreover, as for Federal preemption, should Capitol Hill finally pass a bill overriding state NIL statutes, the commission instantly gains the supremacy it now lacks. Lastly, if shield-law states like Tennessee buy in and/or sign the loyalty pledge, the cap has a fighting chance. If they do not, the settlement era could dissolve into 50-state free agency by 2026.

Commissions, done right, supply the wiring that lets a complex ecosystem function. Done poorly, they become what Bilas fears: one more white paper gathering dust. As House implementation races toward July 1 (now minus a White House backstop), college sports are about to discover which version they get.