As Lawsuits Against the NCAA Continue to Pile Up, It is Clear That the House Settlement is Not the Answer

Although both sides in the groundbreaking House v. NCAA settlement agreed to settle. The NCAA and the overall landscape is more uncertain now than it has ever been before. Even if both sides can agree to a proposed settlement - which they have not yet been able to do so - the NCAA is still facing numerous other lawsuits pertaining to (1) athletes’ name, image, and likeness (NIL), (2) athletes’ employment status, and (3) athlete’s ability to be directly compensated for their athletic endeavors, among other issues. The NCAA hopes that the House settlement, if approved, could hold together a system that is seemingly breaking. However, it is merely a temporary fix that (at best) delays the inevitable - a shift from the NCA'A’s current model that equally treats all college athletes as amateurs.

In the months following the announcement of a proposed settlement that would retroactively pay athletes around $2.8 Billion, and create a revenue-sharing payment system that would allow schools to pay their athletes directly, there has been multiple legal developments surrounding the NCAA. For starters, two lawsuits were recently filed by two groups of former college basketball players - one led by Mario Chalmers and the other led by the famous 1983 NC State National Championship team - against the NCAA for the unauthorized use of their name, image and likeness. As it stands, the two groups of plaintiffs would not receive a dime under the current settlements $2.8 billion proposal.

In addition, two ongoing lawsuits against the NCAA - Johnson v. NCAA and Fontenot v. NCAA - had recent developments that could lead to more trouble. In Johnson v. NCAA, the plaintiffs are arguing that they were employees of their school and the NCAA within the meaning of the FLSA and state law. As a result, the plaintiffs believe they were entitled to (at least) minimum wage for their labor as well as overtime pay. Recently the Third Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the NCAA’s motion to dismiss the case, essentially rejecting the NCAA’s longstanding position that student-athletes cannot be employees and athletes at the same time.

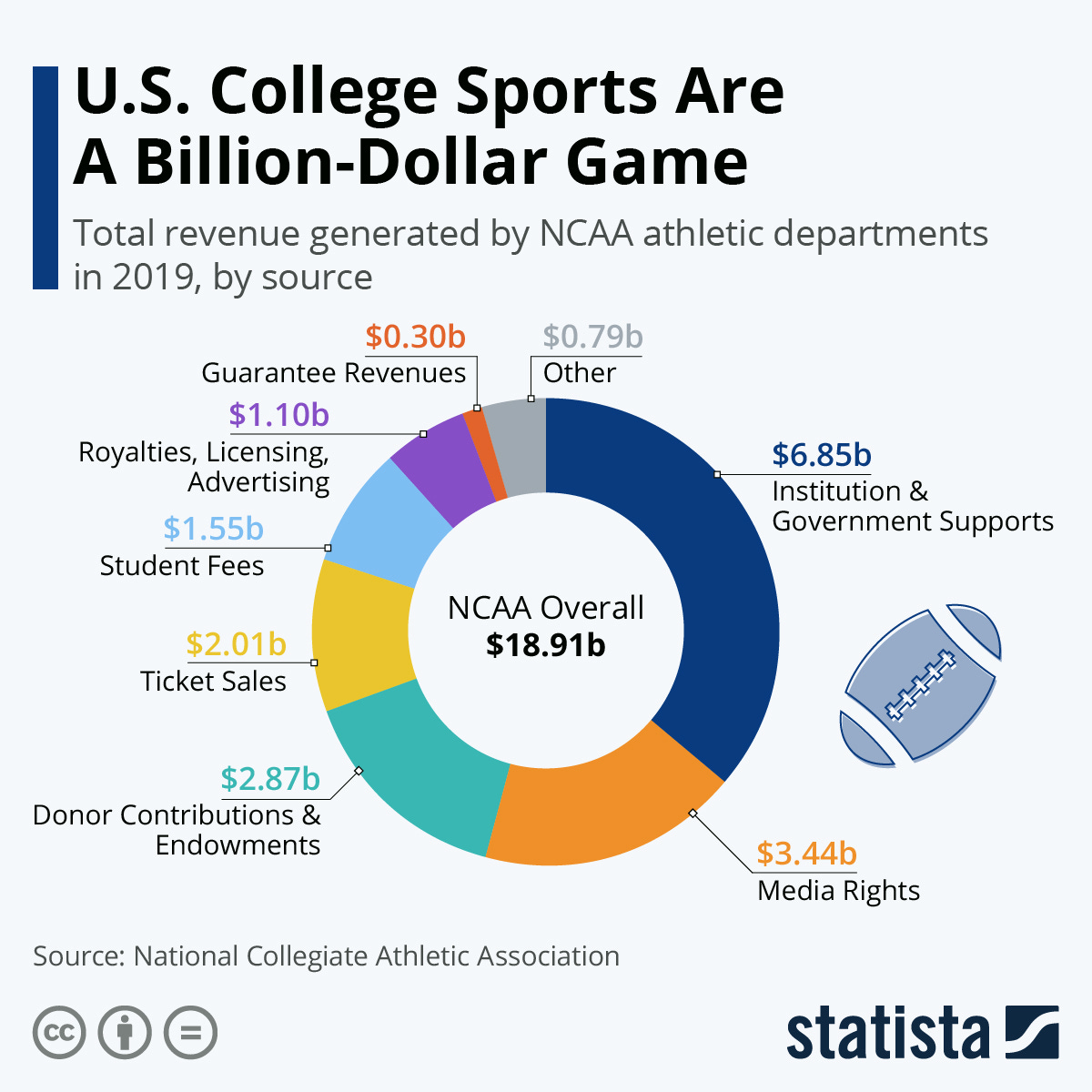

Furthermore, the Fontenot case - which the NCAA believes should be dismissed as a result of the prospective House settlement - recently added four new plaintiffs as well as an amended complaint addressing why their case should proceed despite the House proposal. The Fontenot case challenges the NCAA’s Bylaw 12, which prohibits athletes from receiving direct compensation related to their athletic endeavors, and it specifically targets the NCAA’s billions of dollars in television revenue. Ultimately, the Fontenot plaintiffs believe that the House settlement “would simply usher in a new, artificially low cap that is far below the revenue sharing that a competitive market would yield” if it is approved. “While it is an admission that amateurism is not needed, it also simply substitutes one illegal price fix for another.”

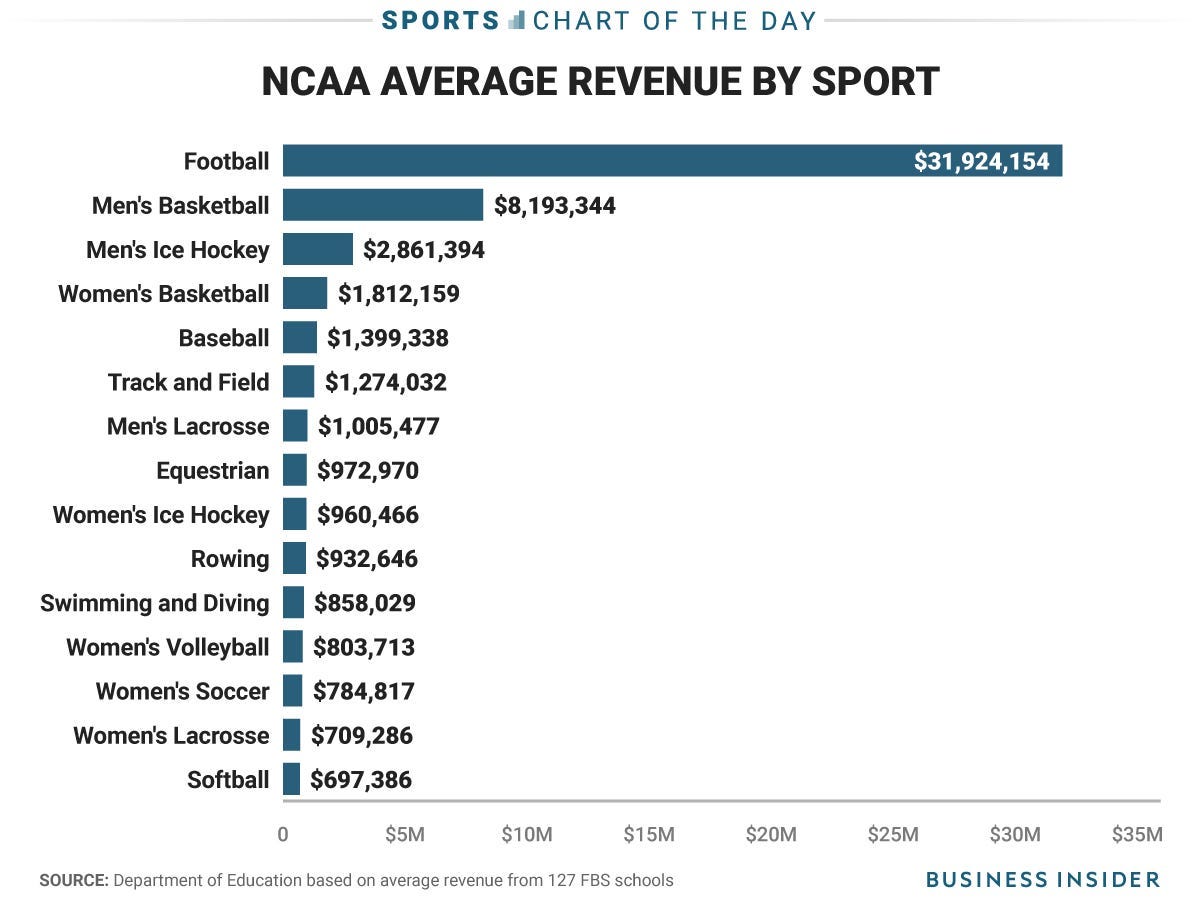

Whether or not the House Settlement is approved, the issue still remains that the current college landscape is obsolete. The NCAA governs all college sports, all divisions of play, and all the conferences and teams within those divisions. Each of these segments and factions bringing in vastly different ranges of revenue. For example, the average school generates $31.9 million in football revenue each year while the next 35 sports on average generate $31.7 million combined. In addition, the University of Texas - one of the top revenue-generating schools - has approximately 70% of their atthletic revenue come from football.

Nonetheless, the NCAA treats each athlete from each division, conference and sport the same. College athletes are not deemed employees (as Johnson v. NCAA argues against), they are not currently eligible for direct compensation and/or an equitable share of compensation (as the Fontenot case argues against), and all other rules and regulations that apply to one athlete (pertaining to transfers, scholarships, etc.) apply to every other athlete.

Ultimately, these sports are not the same, and the emergence of NIL money has proved this. Many College Football and Basketball players are now making hundreds of thousands of dollars through their name, image, and likeness. Meanwhile, most athletes in most other sports are not making anything. The NCAA cannot continue to govern under a system that pretends that all sports and their respective athletes are created equal. Until the NCAA acknowledges these differences, and works to create a solution with these differences in mind, the strength of the association will continue to deteriorate.